The MV Bretagne docked in St Malo under lead-coloured skies and a thin drizzle. This was not how I expected or wished my trip to begin. The plan was to find the V2 cycle-route across Brittany and to follow it to my first stop at Saint-Germain-sur-Ille. The cyclists were disembarked first, to the evident irritation of vehicle-drivers and we filed down the ramp, a pretty motley bunch, the eldest of whom must have been in his eighties, a stringy old bird with a chirpy manner and the oddest assortment of clothing you could imagine.

I rode to the town and took a quick look around. It appeared more like a stage set than a living community and I decided that there was nothing to detain me any further there. I went down to the jetty from which the St Malo - Dinard ferry leaves and found that the next boat was due to leave in over an hour. I chose therefore to go to the beginning of the cycle-track by road. Thus my grand intentions of steering religiously clear of routes bearing motorised traffic fell at the first hurdle. The ride around the coast via the Barrage de la Rance (the only tidal power-station in the world)

was nerve-wracking as there was absolutely no provision at all for cyclists, and lorry-drivers, in particular, seemed to be out to get us. I was only just beginning to get used to my front-mounted load and wobbling quite a bit. So I was very relieved to find access to the piste cyclable just south of Dinard. Once on the piste everything changed. The weather started to perk up and the traffic became a distant memory.

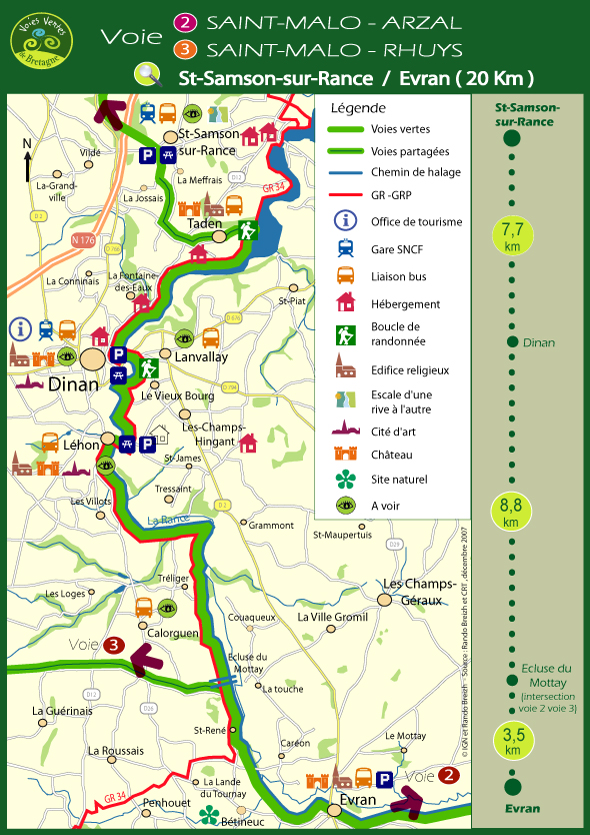

The surface of the cycle-track, which runs from the centre of Dinard to Samson-sur-Rance on the route of the former Dinard-Dinan railway is a sort of coarse grit for the whole of its length. This surface can at times get a bit waterlogged after heavy rain and at some points, the effect can be like riding on wet sand. But it appears to drain quickly and soon the going was tolerably easy.

My new nobbly Panaracers slowed me down appreciably, but I doubt very much whether slicker tyres would have improved things at all. The track itself rises on a slow gradient out of Dinard and runs in long straight lines due south.

I only ran into trouble at one point on the whole length of this particular track and that was just south of Pleurtuit where an underpass under a road had been built for the cycle-track without apparently any thought having been given to drainage. The tunnel had a few inches of water in it and under the water was a thick bed of sticky mud. I hit this at speed and came to a grinding halt in the middle of the underpass, at which point I had to put my feet in the gooey mess and push myself out the other side.

Between Samson-sur-Rance and the tow-path along the Rance itself, the route is well marked and there's no chance of getting lost. There's a bit of the river-bank to do between Taden and Dinan before one gets to the tow-path of the Canal d'Ille-et-Rance proper that constitutes the next stage of this particular route across Brittany.

The path into Dinan is very pretty and the town itself fairly easy on the eye.

Short of tackling a steep climb, however, it's difficult to visit anything but the touristy bit down by the river. This is pleasant enough though quickly visited. A coffee in a bar was about all I could manage before continuing along the chemin de halage. I didn't stay long because there was a bunch of raucous Brits on the terrace, already drunk at this time.

At Lehon, I almost ran into a lady who had set up her easel and paint-box right in the middle of the cycle-track in order to paint the abbey. She took a step back from her painting just at the wrong moment and I had to swerve to avoid her and left her looking daggers at me.

After Lehon, the weather perked up considerably and the track dried out. I made rapid progress and was in Evran for lunch. I sat on the canal-side and munched the cheese andsaucisson sandwiches I had made from rather dubious-looking provisions bought from the only shop open in Evran - a little delicatessen the gloomy interior of which didn't allow any close inspection of what was for sale. I think the shopkeeper had been waiting for a character such as me in order to offload his dodgy wares. Across the canal a bunch of school-children shouted abuse, secure in the knowledge that there was no way I could approach them.

Encouraged by this to finish my lunch, I polished off my faintly rancid sandwiches and set off for Saint-Germain.

The tow-path is a very interesting ride because it becomes obvious that this canalised river was state-of-the-art transport technology at the begining of the nineteenth century when Napoleon I authorised its construction on the 21st of pluviôse of the year 11, in response to threats of a blockade by the perfidious English. The bridges, lock-keepers' houses and the locks themselves testify to a single, co-ordinating design.

After the famous Eleven Locks of Hédé, the cycle-track joined the GR 37 footpath and left the canal-side proper. It also became noticeably less bike-friendly with ruts, tree-roots and deep puddles to make the going tough. It was at this point that a thunder-storm arrived. I was under the trees near the Bassin de Bazouges and hadn't noticed the arrival of the black clouds. But once the rain set in it was of the wettest variety possible and I was soon soaked to the skin despite my waterproofs.

By the time I got to Montreuil-sur-Ille, the sun had come out again. But I was seriously wet and I stopped to take rueful stock of my situation. I was disastrously unprepared for the rain. Every stitch of clothing was soaked. My shoes were full of water and squelching disagreeably. The banana-bag around my waist containing all my documents, money and camera was also soaked. However, everything wasn't entirely swamped. I'd had the foresight to put all of my spare clothes in waterproof bags inside my panniers, so all of the contents of these were perfectly dry. I stopped in Montreuil at a supermarket and squelched in leaving puddles of water behind me to buy some provisions for my dinner, since I knew that Madame David at the chambres d'hôte of La Touche Allard didn't provide any. [ see:http://www.latouche-allard.com/ ] I made sure I got a good bottle of Médoc as compensation for my soaking and for the prospect of a fairly dismal evening meal.

I arrived at Saint-Germain-sur-Ille which is just south of Montreuil at around six. Madame David turned out to be a motherly little woman who quickly agreed to wash and dry out all of my soaking things. The accommodation is more gîte than chambre d'hôte, but comfortable nevertheless and reasonably cheap. The establishment is a working farm, producing kiwis, and the accommodation is in converted farm-buildings. The interior is a little gloomy, but perfectly decent. I shared this space with a chap who had just found work in the area. He was a melancholy sort of bloke who told me numerous tales of French discrimination against the Bretons such as the disproportionate number of Breton deaths in the wars and the origin of the verb baragouiner (to babble incoherently) in the Bretonwords for 'bread' and 'wine'. Uncharacteristically for a Breton he didn't drink much, so I finished the bottle of Médoc single-handed and retired gratefully for the night, in readiness for a very early start the following morning.